Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL)

What is the LCL?

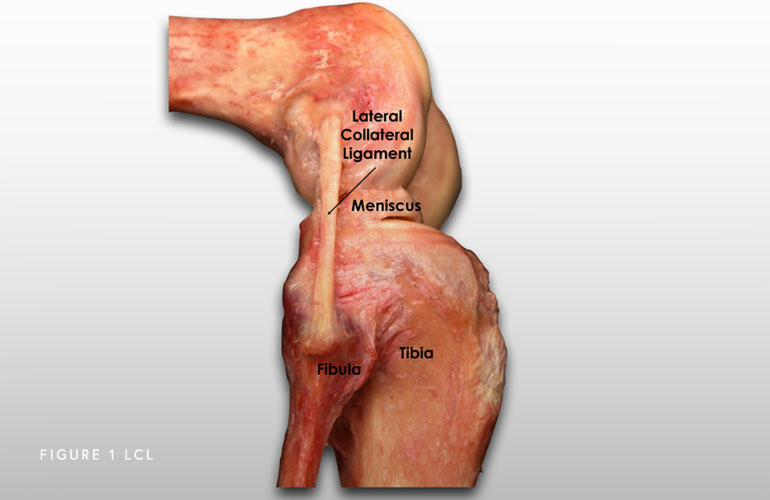

The lateral (fibular) collateral ligament (LCL) is a structure that stabilizes the lateral (outside) side of the knee connecting the thigh bone to the fibula (smaller of the two lower leg bones that sits on the outside). It prevents forces applied to the inner side of the knee from gapping open on the outside.

What is the posterolateral corner of the knee?

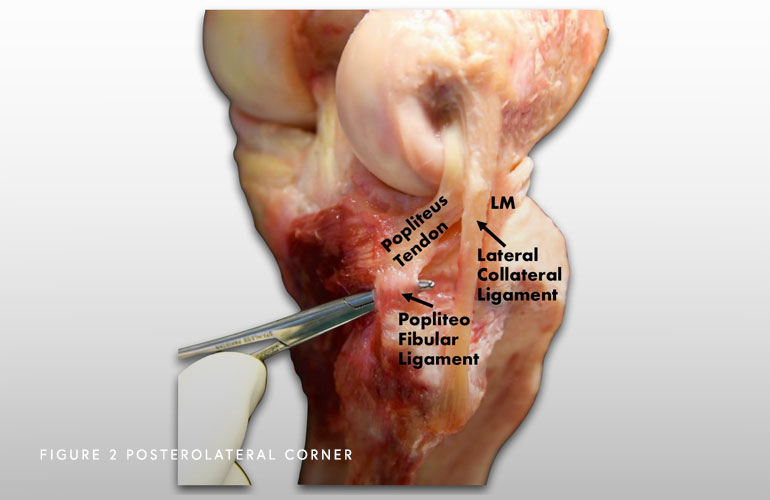

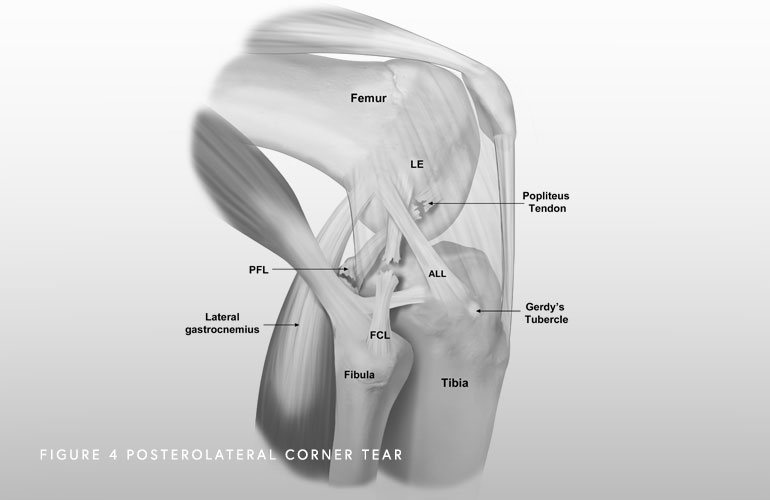

Once known as “the dark side of the knee” because doctors did not have a clear understanding of the anatomy and biomechanics. It is now a well-recognized cause of disability and disfunction. Recent anatomic and biomechanical studies have helped develop new surgical techniques to reconstruct the torn ligaments in their anatomic location (right where they belong), which has resulted in greatly improved surgical outcomes for this part of the knee. There are three primary structures that comprise the posterolateral corner of the knee: the LCL, the popliteus tendon, and the popliteofibular ligament.

How does the posterolateral corner work?

All these structures work together to stabilize the outside of the knee. The LCL is like a tight rope that prevents your knee from gapping open on the outside of the knee. The popliteus tendon and the popliteofibular ligament prevent the tibia (shinbone) from externally rotating (outwards) on the femur (thigh bone).

How do posterolateral corner injuries occur?

PLC injuries can occur in several ways including contact (i.e. hit/blow to the inside of your leg, car accident) or noncontact injuries (falling on a hyperextended knee (knee bends in the opposite direction – backwards), for example in cases of gymnasts or people with overweight). These injuries allow the outside of the knee to gap open (varus gapping), as well as the increased external (outside) rotation of the lower leg (tibia).

Sometimes, the nerve that is very close to all these structures (the common peroneal nerve) can be affected. This is a highly debilitating injury that needs to be assessed as soon as possible by an experienced surgeon. This injury can sometimes lead to a foot drop (you cannot lift your foot/toes up towards the ceiling) because the nerve is damaged. Sometimes, the nerve can be decompressed restoring full function. Sometimes it is permanently damaged, and a tendon transfer (transferring a tendon from another part of the knee) can be done to help with the foot drop to make walking easier.

Symptoms of an LCL Injury

Patients can present with swelling and pain on the outside of the knee. Cases that were not diagnosed at time of the initial injury, can present with difficulty stopping and cutting, or sensations of instability when shifting side-to-side. Additionally, athletes note that they cannot stop and cut towards the affected side when they have the LCL tear, as they feel that their knee is unstable.

Do posterolateral corner injuries of the knee heal on their own?

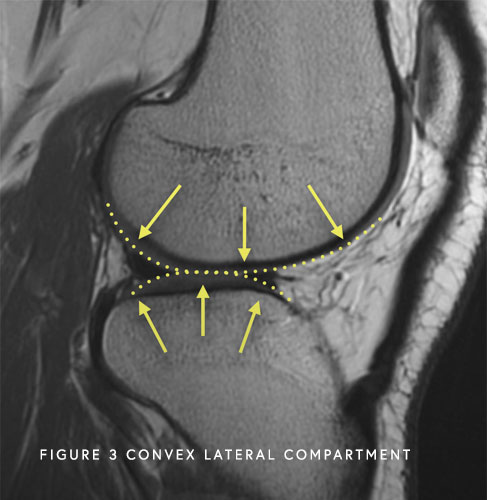

Most of the time injuries to the PLC do not heal on their own because the thighbone and the shinbone (lateral femoral condyle of the femur and lateral tibial plateau of the tibia) are both convex (round) which makes this part of the knee inherently unstable if the ligaments and tendons are damaged. Thus, these injuries should be seen and treated quickly to achieve the best outcomes.

Additionally, almost all complete PLC injuries occur with injuries to other knee ligaments. When additional ligaments are involved, surgical reconstruction is required to restore the anatomy.

If you wait six weeks or longer to be treated and you are bowlegged (most men are slightly bowlegged), an osteotomy, or a surgical correction of the bowleggedness, may be needed before proceeding with the ligament reconstruction, to make sure that the surgical reconstruction does not stretch out.

From the Knee Injury Bible. LaPrade, Chahla, O’Brien and Kennedy.

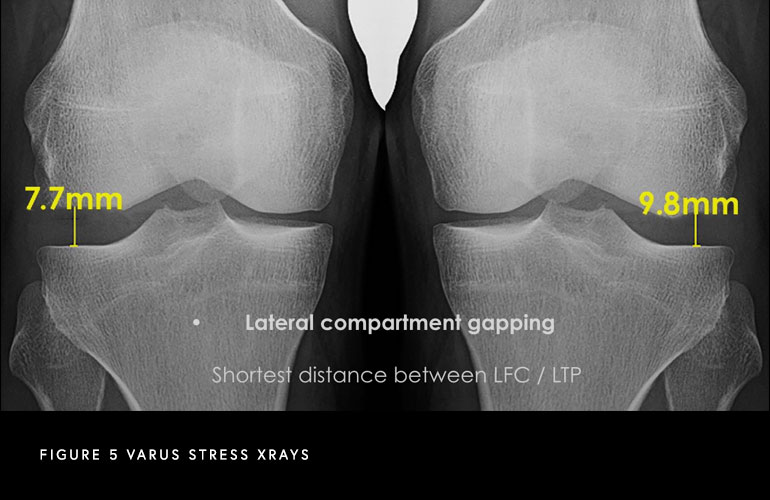

What is the most accurate way to diagnose a posterolateral corner injury?

A combination of a comprehensive physical examination, special x-rays, and magnetic resonance imaging are of utmost importance to diagnose these injuries. One special x-ray that we perform to determine the severity of your pathology are called stress x-rays. This special x-rays allows us to objectively quantify and diagnose (based on validated thresholds) a posterolateral corner injury with millimeter accuracy.

What is the best time to fix a posterolateral corner injury?

Dr. Chahla helped establish a global consensus on the treatment of posterolateral corner injuries. Surgeons from around the world agreed that Grade 1 and 2 tears can be treated nonoperatively with physical therapy, while Grade 3 tears should almost always treated with surgery. When there is a complete tear of the LCL, or when all the structures of the posterolateral corner of the knee are injured, surgery should be pursued within the first two weeks after injury, and once range of motion has been recovered. This is the best time to repair the structures, before there is significant scar formation, or the tissues become weakened. The position and alignment of the knee can also be anatomically restored (brought back to the normal state) during that time frame, rather than delaying and allowing the knee to heal in an abnormal position. Recent reconstruction techniques have allowed many patients to get back to high-level activities. This was not true in the past, when a posterolateral corner injury would typically end further sports participation or even limit participation in normal activities because of ongoing knee problems.

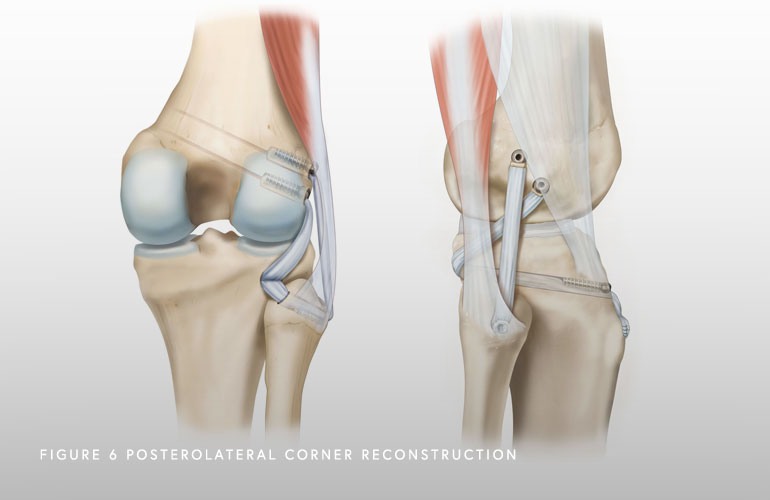

How is the posterolateral corner fixed?

We believe that restoring the anatomy (putting everything where it belongs) can produce better outcomes. There are multiple techniques described. However, we perform one technique that restores all the native insertions of the posterolateral corner, which allows for early range of motion and has been proven to result in excellent outcomes.

How long is the recovery?

Depending on the severity of the injury and the associated injuries, recovery can take between 6 to 12 months. Physical therapy starts on day 1 to work on range of motion. Patients should not bear weight (or very little weight bearing) for the first six weeks after injury. They then initiate a partially protected weight-bearing program (with crutches) at the six-week point, and may wean off of crutches when they can walk without a limp. Driving on the operative knee is usually allowed at about seven to eight weeks postoperatively. Endurance and strengthening can be started in the second phase of the rehabilitation. Agility exercises start at 4 months along with the running progression if previous stages have been successful. Although return to sports changes between patients, it should be allowed at approximately 9 to 12 months.

At a Glance

Dr. Jorge Chahla

- Triple fellowship-trained sports medicine surgeon

- Performs over 500 surgeries per year

- Assistant professor of orthopedic surgery at Rush University

- Learn more